Definition

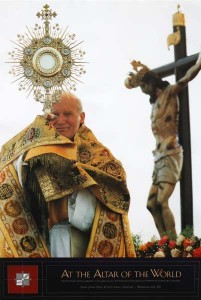

Eucharistic Adoration is a sign of devotion to and worship of Jesus Christ, who is believed to be present in the consecrated host. The consecrated host is the physical presence of Christ in the sanctified bread and wine which Roman Catholics (and Anglo-Catholics) believe to be the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Transubstantiation

The consecrated host/bread is placed in a monstrance and stationed on the altar for viewing at regular times during the week. The devotional and worship practice of adoring and praying to the consecrated host is practiced in local parishes, shrines, and monasteries. The belief that Christ is physically the wafer/host as displayed in the monstrance and is present in the midst of the congregation is a theological extension of the doctrine of transubstantiation. Without exception, those Roman Catholic (and Anglo-Catholic) churches who endorse Eucharistic adoration accept as true the doctrine of transubstantiation.

The doctrine of transubstantiation is the belief of the Roman Catholic Church that the outward (accidents) appearance of the bread stays the same after consecration, but the host’s inner nature (substance) is changed into the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. These categories of accidents and substance are the thought of Aristotle not the theological workings of the Ancient Fathers of the Church or the biblical teaching of Jesus Christ and Paul the Apostle.

Medieval Development

Eucharistic adoration is not an ancient practice; it began in Avignon, France on September 11, 1226. Public adoration of the Blessed Sacrament began as a thanksgiving celebration for the victory of France and the Roman Catholic Church over the Albigensians in the later battles of the Albigensian Crusade. King Louis VII desired that the sacrament be placed on display at the Chapel of the Holy Cross. The multitude of adorers brought the local diocesan bishop, Pierre de Corbie, to suggest that the display continue indefinitely. With the permission of Pope Honorius III, the idea was approved and adoration continued mostly uninterrupted until the French Revolution.

Genuine Catholicity?

Eucharistic adoration is not encouraged in the Orthodox churches of the East neither has this form of worship been practiced everywhere for all the time by all churches. For a practice or doctrine to be considered orthodox: it must have been received by the undivided Church (East and West), stood the test of time, and agreed upon by the consensus of the early fathers. This triple test of ecumenicity, antiquity, and consent is called the Vincentian canon and it is the overarching test for genuine Catholicity. In my view, the practice of Eucharistic devotion, that is displaying a monstrance containing a consecrated host for worship and prayer, does not pass the test of the Vincentian canon. Therefore, Eucharistic devotion does not meet the criterion as an acceptable practice within the Great Tradition and is not to be considered a theological conviction of the Ancient Faith.

Russian Orthodox theologian, Alexander Schmemann, states that Eastern Orthodoxy does not practice the elevation of the bread and wine for special adoration.

The Purpose of the Eucharist lies not in the change of the bread and wine, but in the partaking of Christ, who has become our food, our life, the manifestation of the Church as the body of Christ. This is why the gifts themselves never became in the Orthodox East an object of special reverence, contemplation, and adoration, and likewise an object of special theological “problematics”: how, when, in what manner their change is accomplished.

[Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist: Sacrament of the Kingdom (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 1998), 226.]

Eastern Orthodoxy’s Eucharistic focus is not on the change in the elements, but on the presence of Christ, the power of the Holy Spirit, and the mystery of faith encountered in the ancient liturgy. Eastern Christians do not adore the consecrated bread outside the liturgy itself.

The Reformation

As would be expected, the Evangelical Reformers of the sixteenth century had grave doubts about the practice of Eucharistic adoration. They decried its use, discouraged participation, and condemned the practice within Reformed churches. John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli and their colleagues in Geneva and Zurich, respectively, issued a statement as to their common agreement concerning the nature of the Lord’s Supper. The document, Heads of Agreement on the Lord’s Supper, was written after the failure of the Marburg Colloquy.

The Marburg Colloquy was an attempt to achieve a concord between Martin Luther and Zwingli over the nature of the Eucharist. Luther believed in Real Presence of Christ (physical) and Zwingli declared the elements of bread and wine to be merely symbolic. Luther and Zwingli’s disagreement was volatile and very public. Their discord was rending the Protestant movement at its very heart.

John Calvin felt that Protestantism needed at the very least to declare its unity on some matters regarding the Lord’s Supper. Article Twenty-Six states Geneva and Zurich’s condemnation of Eucharistic adoration:

If it is not lawful to affix Christ in our imagination to the bread and the wine, much less is it lawful to worship him in the bread. For although the bread is held forth to us as a symbol and pledge of the communion which we have with Christ, yet as it is a sign and not the thing itself, and has not the thing either included in it or fixed to it, those who turn their minds towards it, with the view of worshipping Christ, make an idol of it.

The rejection of the practice of Eucharistic Adoration by the Magisterial Reformers continues to be doctrinal belief of all Evangelical churches everywhere.

Idolatry

Many Roman Catholic (and Anglo-Catholics) are sincere in their desire to dwell in Christ’s presence, but it takes very little effort on the part of the Enemy to turn this sincere devotional activity into a form of idolatry. Roman Catholics describe the consecrated host as “the physical Body of Jesus” and that the presence of the host increases the anointing in the sanctuary, because Christ himself is contained in the physical object of the wafer. It is said, if the monstrance is removed, God’s presence is removed. If “the host and precious blood” are returned to the sanctuary, it is said that Christ presence has returned.

To state that God’s presence is contained or limited within a physical object is a form of idolatry (Exodus 20:4-6). Idolatry reduces God the Creator to a material object of creation thereby limiting his attributes of omniscience, omnipotence, and omnipresence. The Lord is no longer Spirit, but an object which can be controlled by human beings (Isa. 40:18-23). It grieves me as a believer, pastor, and theologian, that God’s precious gift to us of Holy Communion has been twisted and made into an object of limited worship. I have no doubt that that the adorers are sincere in their desire to be in the presence of Christ. However, it will not take long for the flesh, or the Enemy, to bring misunderstanding about the nature of the Holy Trinity causing much personal sorrow and emotional pain to all involved. Arguments that Eucharistic adoration is a blessing to parishioners by increasing the presence of God in the church building is experiential and subjective without basis in scripture or tradition.

The Ancient Liturgy

Instead of the Table of the Lord being a place of participation in Christ, it becomes a night stand for observing God from a distance. Adoration confuses the physical object with its Author, and the location of God with a material entity, and limits God’s attributes to a place and time. Alexander Schmemann’s main criticism of Eucharistic adoration is that the practice isolates the Eucharist from its purpose: communion with God (pg. 227). The Eucharist is removed from its context in the liturgy as the communion of the Church with Christ and places Christ at a distance, objectifying the Eucharist in a manner not consistent with the whole meaning of the Lord’s Supper.

Holy Eucharist is intended to be place of an encounter with the living resurrected Christ. In Scripture, seven theological images or truths of the Eucharist are revealed: remembrance, communion, forgiveness, covenant, nourishment, anticipation, and thanksgiving. These truths cannot be experienced if we are watching instead of participating.

Summary

Eucharistic adoration as a belief and practice is erroneous: it does not reflect the teaching of the Bible or life of worship found in the Ancient Church. The practice is not promoted in the Orthodox East and is not consistent with full and complete participation in the Holy Eucharist.

Caveat: The views expressed in this blog post are entirely my own and are not necessarily the views of the Central Gulf Coast Diocese, Southeast Province, or the International Communion of the Charismatic Episcopal Church (C.E.C.).

Very concise and authoritative article!

Would you speak for just a moment on Luther’s concept of Consubstantiation…?

I think Consubstantiation holds that Christ is present in the bread and wine during the service, but at the end of the service revert back to just bread and wine.

Or is this similar to the Orthodox view that the bread and wine are changed into the body and blood of Christ, but the manner of how this change is accomplished has not been revealed.

What about Richard Hooker in Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie when he said “the Real Presence of Christ is to be found in the one receiving and not the elements”. ergo If one receives the Eucharist with trusting Faith then one receives Christ in the Eucharist, if someone receives who has no faith or trust in Christ then all they receive is bread and wine, nothing more, but in so doing they insult Christ by receiving without faith.

I know this all over the place, but this subject has always held a place of interest for me… your responses will be greatly appreciated…

By the by…

Some of John Hooker’s writings can be found here:

http://anglicanhistory.org/hooker/

Sorry

*RICHARD* Hooker

Joshua:

I apologize for being so tardy in responding to your comments. My “off-days” from Best Buy have been taken up with matters relating to acquiring the new church building on Morgan Road.

Consubstantiation was Martin Luther’s explanation of how the bread and wine are changed into the body and blood of Christ at the prayers of institution. Theologian, Wayne Grudem describes Luther’s view:

“Martin Luther rejected the Roman Catholic view of the Lord’s Supper, yet he insisted that the phrase “This is my body” had to be taken in some sense as a literal statement. His conclusion was not that the bread actually becomes the physical body of Christ, but that the physical body of Christ is present “in, with, and under” the bread of the Lord’s Supper. The example sometimes given is to say that Christ’s body is present in the bread as water is present in a sponge—the water is not the sponge, but is present “in, with, and under” a sponge, and is present wherever the sponge is present. Other examples given are that of magnetism in a magnet or a soul in the body.

The Lutheran understanding of the Lord’s Supper is found in the textbook of Francis Pieper, *Christian Dogmatics.* He quotes Luther’s Small Catechism: “What is the Sacrament of the Altar? It is the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, under the bread and wine, for us Christians to eat and to drink, instituted by Christ Himself.” Similarly, the Augsburg Confession , Article X, says, “Of the Supper of the Lord they teach that the Body and Blood of Christ are truly present, and are distributed to those who eat in the Supper of the Lord.”

[*Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine* (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 994.]

Luther was attempting to maintain the Patristic church’s view that Christ is physically present in the bread and wine while simultaneously rejecting the Roman Catholic understanding of transubstantiation. Luther disliked the Aristotelian categories of substance and accidents and the Roman Catholic “works oriented” medieval piety surrounding the mass.

Timothy George states in his wonderful book, *Theology of the Reformers,* “He [Luther] retained nonetheless a high view of the objective character of the sacraments.”

In regard to Richard Hooker, he was a memorialist in the tradition of Ulrich Zwingli. Memorialism/receptionism states:

*The view of the Lord’s supper believing that the taking of the bread and wine represents a symbolic memorial or a remembrance of Christ’s redeeming work on the cross. This view has its most articulated foundation in the theology of Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531). Memorialism is in contrast to all forms of the “real presence†view which hold that Christ is physically present in the taking of the bread and wine. Memorialism argues that when Christ said “this is my body . . .†that he was speaking symbolically. One of the primary arguments for this view would be that to take it literally would have to mean that the bread and wine were Christ’s body at the time of the first Lord’s Supper, while Christ was yet living, not only following the passion.*

[HT: Theological Word of the Day]

Memorialists believe that it is in the faith of the congregation that Christ is made present not in the “symbols” of bread and wine.

It would be fair to say that neither of these views represent anything close to the Eastern Orthodox position of transformation and the physical presence of Christ.

Luther did NOT subscribe to “consubstantiation.” Nor did the Lutheran Church which subscribed to the Book of Concord of 1580. The example that Grudem gives is not Lutheran either.

Martin Luther may not have used the word, ““consubstantiation,” he did by all intents describe its meaning. Consubstantiation being the “substance” of the body and blood of Christ are present *alongside* the substance of the bread and wine, which remain present and unchanged.

“But why could not Christ include His body in the substance of the bread just as well as in the accidents? The two substances of fire and iron are so mingled in the heated iron that every part is both iron and fire. Why could not much rather Christ’s body be thus contained in every part of the substance of the bread?”

*Babylonian Captivity of the Church,* Luther’s Works, vol. 6.

True, not all Lutherans hold to this view, but Luther did believe in the real presence of Christ in Holy Communion.